Checking in from the field with the Taj, Tipu, Tigers, Toth, Tania, Tolkien, and the Tale.

Were an artist to choose me for his model –

How could he draw the form of a sigh?

(Zeb-un-Nissa, as referenced in Loot, by Tania James)

“Before she died, the empress asked her husband, Emperor Shah Jahan, to promise her four things.”

I waggled my head instinctively and said “mhmm.” Even this slight movement caused a bead of sweat to trickle down my face in the 100+ degree heat.

“One, take good care of our children. Two, remarry. Three, visit my resting place once every year. And four: for my final resting place, build a monument to our love that will last forever.”

Being a good local guide, he stopped walking at this point and allowed my companion and me to gaze up at the Taj Mahal, white marble radiant in the sun, to show that we appreciated the gravity of these words. I did. And, because I’m that type of tourist and that kind of romantic dork, I said, “He kept his promise. At least on that last one.”

“It is said he kept all four,” said our guide with a smile, and we continued on.

I wasn’t being glib. The words of the 17th Century Mughal emperor were inlaid in my mind like carnelian and emerald as we beheld this testament to their love and legacy. Here I was, hundreds of years later, awestruck, moved, just as she would have wanted.

The most beautiful sights that trip were still to come in the hill stations of Munnar, but the Taj is the place I have thought of most. When you are open to such things, sometimes a particular experience can unlock for you a new understanding of yourself, the world, and your place in it. I’ve been turning over my experience at the Taj since my visit and put it in conversation with what I’ve been reading and watching to understand something about what I’m writing. Not what I’m writing now, as in literally this sentence in this blog (though maybe this too), but what I’ve been writing – or, more often, not writing – over the last year and change, the thing I’ve been punching into my father’s Hermes just a few feet away from me.

In the presence of the Taj, quite possibly the most perfect building I have ever seen, I felt the longing a temporary being (“a mist that is here and then vanishes,” according to the Book of James) has for something resembling permanence. Not for me – I’ve got maybe 60 years left if I quit smoking and survive my family’s tragically early demises – but for my legacy, “what’s left of you when you’re gone,” as Tywin Lannister defines it. The opportunity of leaving something behind that lasts. And an opportunity is really all I’m yearning for, just the long shot possibility that something I write will last beyond me.

It’s an inspirational force. An exciting challenge. And a devastating burden.

Standing there in my sweaty kurta, squinting against the dazzling stones, thinking of monuments and legacy, of memory and stories, of love and death, of time and space, maybe the opportunity was already gone.

Microsoft recently published a study ranking, among other things, the ten jobs most threatened by Artificial Intelligence. Fifth on the list was “writers and authors.” Sad findings, but old news; at this point, anyone in creative spaces who thinks AI can’t replace them is kidding themselves. Every art form will, in the near future, be passably imitated by machines, and unless we reject AI art with all the hate in our heart, it is going to be forced on us by wealthy technocrats who don’t care at all about the actual art being produced.

If (when) the day comes that AI art is a socially-accepted fact of life, I’ll still write. The monetization of hobbies has made it difficult to remember that humans are meant to do things like sing, dance, paint, play, and tell stories even if they’re not getting paid to do so. Until the day I die, I will be writing things down, even if there are no longer people who want to read it. But, alas, I’ve gone and shared my writing too many times not to be addicted to the feeling. Every time someone reads one of my blogs or novels, I drink from the cup of embarrassment and apprehension, but the finish is rich in gratification, in affirmation, in exhilaration, and each drink only deepens the thirst. I can’t get enough, and at least for now the idea of no longer sharing my writing with others scares the shit out of me. I’ve long given up the dream of being a full-time writer, but not even being able to try, to, again, not even have the opportunity…that is a horrible outcome to ponder.

It’s not exactly a secret, but this serves as the official announcement: I’m writing a sequel to The Hunter’s Tale. It’s called Lives We Might Have Lived and is due out 2026 if I can bring myself to do it. I hate this term, but I suppose I’m experiencing what you may call “writer’s block.” It’s not because I don’t know what to write; I actually know almost every step of the way between where I am now (probably about halfway through a first draft?) and the end. I have envisioned the final scenes in my head hundreds of times. But I can’t bring myself to write it for three reasons.

One, it’s a real struggle for space right now. I won’t list all the things I have going on, because most people have just as occupied. I just mean to say what any writer with a full-time job will tell you: there’s only so much of me available. And in these dark days, time, energy, and resources all feel so loose in our hands. There has never in my life been a more important time for people to strategically use what’s available to them, because if we are apathetic the wicked people running this country will continue dragging us into worse and worse places. But, at the same time, what is available to us also feels so insignificant, so meaningless, so futile, in the face of that wickedness. I work with international students, so every day I’m having to choose to try my best even when my entire job field might be eliminated in the near future.

Two, writing a sequel is daunting, especially when that sequel is the follow-up to the book of mine that has been by far the most popular. Yours Truly and Other People’s Pain are both much better books and more personal to me to boot, but they have, by and large, been massive flops, while The Hunter’s Tale has been much, much more well-received. It’s a meaningful book to me, but I have also been aware of its shadow as I worked on the next two projects, and at times have even resented it because of its (to me) outsized reputation.

The skeptic might say that I’m writing a sequel to capitalize on the original’s popularity. A completely reasonable assumption to make, but wrong. Though I have had people ask me about a sequel, it was never something I was interested in returning to, even if I had thought a little about what would happen to the characters next.

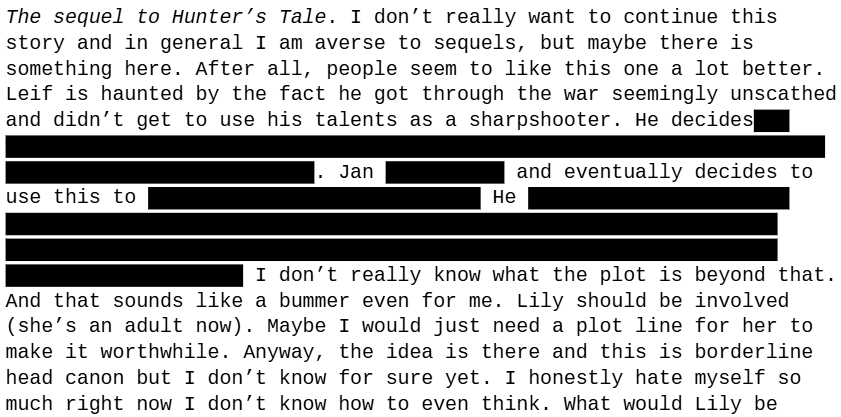

In January of 2024, just a few weeks before I would go to India for the very first time, I went to my favorite coffee shop and wrote out the ideas I had for my next novel in a self-deprecating brainstorm session. About the possibility of a Hunter’s Tale sequel, I wrote:

Moving on.

In the nearly two years since I wrote that, the story has revealed itself to me, but I can’t really identify any of the points along the way where I learned what was going to happen. One moment I was wondering what would happen if Leif went back to Afghanistan and the next I had a neo-Western at the tips of my fingers. I don’t even remember when, why, or how I came up with the title. But here I am with a story that is much bigger and bolder than Tale.

I had some reservations about going back to Leif and Jan. Leif is my least offensive main protagonist and Jan is probably my greatest achievement in character building. Readers love Jan. I wanted to leave them alone, safe and warm together with Lily. And Lily, being a teen in Tale, she could’ve stayed like that with boundless opportunities ahead of her. Instead, I’ve reached out and dragged them back into another story, one that is, I can assure you, much more harrowing than the happy endings I imagine some readers had in mind for them.

I want to get it right. I have to get it right.

And three (please excuse the extended tricolon), I was working on writing this blog post.

I don’t blog anymore, not really. Since my move to Milwaukee, almost all my posts have been reviews of the year in film and existential life updates connected to my travels in India. Once again, after my fourth and fifth trips to the subcontinent, my experiences abroad have helped me think deeply about some aspect of my life. And, quite conveniently, given me a chance to talk some more about other people’s art that means a great deal to me.

So it was important to me to get this blog post written before moving on with Lives We Might Have Lived. This felt like something I “had” to say before I could clear my mind enough to lock in and get through the first draft, which I intend to be by Christmas. It’s just been hard to get to the writing of this post because first I had to rewatch a long movie, reread a normal length book, and make use of the small amount of time I have left when the dishes and laundry are done.

“Taj Mahal is nothing,” said one of my Indian friends. “There are much better places in India. Meenakshi Temple is much more impressive. Jagannath, many others. Taj Mahal, Charminar, these are famous frankly because Muslims have marketed them well.”

“How do you spell that, Meenakshi?” I said, opening my “places to visit in India” note and brushing aside the casual Islamophobia that is unfortunately so common in India.

“And, I don’t know,” I said. “I thought the Taj was pretty amazing.”

“Oh, it’s very good, of course.”

“You just said it was nothing.”

“I may have overstated.”

I think hundreds of years of awestruck visitors is due not so much to Muslim marketing as it is to the fact that, as Yves Saint-Laurent said, “Fashion fades, style is eternal.”

I have seen buildings that are great in ways different from the Taj. Ornate basilicas, hulking stadiums, glorious monuments. But none of them are, well, perfect, as the Taj is perfect. Its form is its function and its function is its form. There is no wasted space, no wasted effort, nothing to “get,” nothing to miss. I wonder if there is a building that more closely approaches timeless, objective beauty.

This is central to one of the best films of 2024, Brady Corbet’s The Brutalist (light spoilers ahead). The film follows Laszlo Toth (Adrien Brody), a Holocaust survivor who comes to the U.S. in the 1950’s for the promise of freedom. In Hungary, he was a renowned architect, but he must start from nothing in the U.S. fashioning uninspired furniture in his cousin’s shop, praying for the day his beloved wife and niece may join him.

Much of the drama comes from the push and pull of artistic vision between Toth and his eventual benefactor, Harrison Van Buren (Guy Pearce), a relationship which is a college seminar on its own. When Toth gets the opportunity to redesign Van Buren’s reading room without his knowing (a misguided surprise gift form his son), Van Buren flies into a rage and berates Toth and his cousin for what they’ve done. Interestingly, it is in response to this tirade that we first see confidence and swagger from Toth, who to this point has been defined by fear, humility, and meekness. He knows what he built is good, even if the person he built it for doesn’t see it the same way, and throughout the film it is only when talking about his art that we see this same swagger.

After Van Buren discovers Toth’s accomplishments in Hungary, he not only apologizes to Toth but invites him to his home and commissions him to build a community center in honor of his late mother. Two of the many examples of the ways in which Van Buren misunderstands Toth’s vision are in this first reception at the Van Buren mansion. Though there are many wealthy, influential people at the party, Toth is the guest of honor, and Van Buren gives him much of his time and attention. At one point as they speak privately over drinks and cigarettes, a guest interrupts to express his admiration of the reading room, making an astute observation about how the design draws the viewer’s attention, which as we will learn is one of Toth’s greatest concerns when designing. Van Buren shows complete disinterest in the man’s comments and rebukes him for interrupting. Then, Van Buren opts instead for a very general question: “Why architecture?”

Watch the scene for yourself:

It’s one of those monologues I will think about for the rest of my life. “Is there a better description of a cube than that of its construction?” To me, Toth’s buildings – like most Brutalist style buildings – are ugly, all the more so because he typically uses concrete. The film even acknowledges this when Leslie asks why they don’t build the community center out of something more aesthetic. But the form of his architecture is remarkable because of its functionality and endurance. Were there more beautiful buildings in wartime Budapest? Of course. Are they still there? Many of them are not. What this means is that a synagogue built by Toth would be from its inception excellent for it’s synagogue-ness, but in its endurance it would maintain the synagogue-ness and take on a political element.

It’s all well-beyond Van Buren, and Guy Pearce’s “what a poetic reply” line reading is quite possibly the greatest moment of his acting career. Missing Toth’s point, Van Buren just moments later will offer Toth a commission that flies in the face of everything Toth just explained.

The singularity of purpose in his architecture makes Toth the absolute wrong architect for Van Buren’s planned community center, an impassioned but Quixotic tribute to his late mother. Van Buren envisions it to be a library, gymnasium, church, and theater. “That is four builds, not one,” says Toth. But Van Buren is adamant Toth must be the one to do it, which again shows his crucial misunderstanding of Toth’s art.

But, short of opportunities, Toth obliges, and the concrete monstrosity is eventually finished, but in the final moments of the film we understand how Toth has insinuated his singular vision into the multivalent blueprint.

The second obvious thing (back to the Taj!) that the Taj has going for it is the material: Marble, Rajasthani marble. Though not as shiny and luxurious as Italian marble, Indian marble is hard, durable, and impermeable, making it resilient through rain, wind, and years, ideal for something like a giant mausoleum meant to stand the test of time. I learned these things from one helluva salesman at a local marble purveyor, and I did walk out of there with a few small beautiful pieces. One of the most incredible traits of marble is that, even in its impermeable forms, it is luminescent (seriously if you have marble try this). The Taj is dazzlingly bright during the day. At night, with the proper lighting, it glows.

Toth’s community center is entirely concrete save for one feature: the altar, which is made of – you guessed it – marble. Though he is Jewish, Toth takes the mandate to build a significantly Christian space seriously, and so he insists on traveling to Italy to source just the right marble for the centerpiece of the build (to you and me, anyway; Toth may see other features as the heart of his work). The time in Italy contains by far the film’s ugliest scene, but also arguably its most beautiful as the local guide shows Toth and Van Buren the way through the marble quarry to the stone he has specially selected. It feels in that quarry that the trio have stepped beyond the circles of the world into another ethereal plane, kept grounded only by the guide’s recounting of anti-fascist resistance in wartime Italy. The marble slab comes to shimmering life with a simple pour of water over its face. It is clear that the marble will be, in true brutalist fashion, a perfect marriage of form and function. A marble altar? It is its own explanation.

The quarry scene also illuminates some aspect of The Brutalist that I think is obscured in the ugliness of concrete, and that is the fundamental awe human beings have for stonework. Though impressive and beautiful in their own ways, I’d argue no building material is as capable of instilling wonder in human beings as stone and stone-like facsimiles (concrete).

Ah, look, a chance to jump onto a Tolkien tangent:

Tolkien loved Creation and the natural world, and his care for everything from the stars above to the depths of the oceans below comes through so overtly in his writing. His greatest love was most probably trees, the domain of the deity (Vala) Yavanna. But he also held a special reverence for rock and stone, the domain of Yavanna’s husband, Aulë . Trees are precious, living things, symbols for growth and renewal. They can be old, of course – very old – but still need nourishment, tending, shepherding. Stone, on the other hand, speaks to a depth of time beyond memory. It is the bones of the earth.

So it is no surprise Tolkien often marks hallowed spaces in his world with stonework. There are the hidden First Age cities of Gondolin (Quenya: Hidden Rock), Menegroth (Sindarin: Thousand Caves), and Nargothrond (Quenya: Fortress on the River Narog). That same Quenya root “ond” shows up in the name Gondor (Land of Stone). And what is the great fortress city of Gondor, Minas Tirith, made from? White stone, akin to the stone the Numenoreans built their great cities out of. I can go on and on – the Stone of Erech, the Halifirien, Khazad-Dum, the Glittering Caves, when Tolkien wants to instill awe, gravitas, ancientry, he uses stone. He never traveled to India, but I am sure if he did he would have been moved by the Taj Mahal.

For all his bluster and superficiality, there are moments where Van Buren demonstrates something close to a genuine appreciation of beauty. In the quarry scene, he stretches his arms across the slab the guide has chosen for them and lightly places his cheek against it. It’s a sort of worshipful supplication in the face of inimitable beauty, an act of complete reverence. I hate to admit that anything Harrison Van Buren does moves me in any way, but I think about this shot often, and it brings me to the next part of this blog and a work of art that is every bit as powerful as The Brutalist.

On my first trip to India, I went with one of my world-traveling friends to a bookstore in Bengaluru he had been to before (Blossom Book House). It was every bit as enchanting as he said it was, with stacks upon stacks of books arranged in dubious order, prompting the bibliophile to browse and search and discover. I walked out with a new (2023) hardcover book that caught my eye because it had tigers (my favorite animal) on the cover: Loot, by Tania James, a leading voice in the literary community of the Indian diaspora (and only 599 rupees so less than $7 why are books so expensive in the US??). The blurb was plenty compelling, especially because it was historical fiction featuring Tipu Sultan, a late 18th-Century ruler whose summer palace we had just visited earlier that day.

Loot is now one of my favorite novels of all-time. And because I want you to read it I’ll avoid spoiling it as much as I can!

It is the story of Abbas, a talented young woodworker in Bengaluru who works with a fictional French inventor (Lucien du Leze) to craft a mechanical tiger for Tipu Sultan. This would be about like if George Washington had asked an indentured servant to help remodel Mount Vernon. A bellows within the wooden tiger allows it to grunt and growl as it sinks its teeth into a supine British soldier, and the connected organ allows music to be played through it as well. Tipu’s Tiger (which is a very real historical artifact) is a rousing success, and Lucien offers Abbas an opportunity to return to France and become his apprentice. It’s all going great for Abbas until General Cornwallis (yes, Tom Wilkins in The Patriot) arrives in southern India and finally tames The Tiger of Mysore (Tipu Sultan), and Tipu’s Tiger is hauled away with the other spoils of war. Abbas begins a journey to reunite with Lucien and the Tiger.

Loot is about many things, and many of those things are meaningful to me personally, but most germane to this indulgent essay is the relationship between art, artist, and audience. Abbas is an artist, and nothing he creates makes him feel so fulfilled as working side by side with Lucien on this one-of-a-kind automaton. It is an expression of himself, and a work so great that he wonders if it might stand the test of time and remain long after he’s gone. If not, it is surely the first step in an artist’s journey towards making the thing that will outlast him. In order to continue this journey, he must find the tiger again and retrieve the proof that he crafted it, a small engraving on the inner mechanism that credits the automaton to him and to Lucien.

Abbas succeeds at long last in finding the tiger again, but discovers that while the tiger means one thing to him, it means something completely different but perhaps just as powerful to its current owner. Abbas clearly has much in common with Toth, and the owner of the tiger turns out to have more than a few things in common with Van Buren, though their eye for art feels much more genuine (and there’s an entire essay to be written comparing those two characters).

When Abbas gets a few moments alone with the tiger at long last, the scene is tactile and spiritual in much the same way as Van Buren touching the marble.

Behind each imperfection is a story only he would know, a story interwoven with his own. He has made other things, admired his own creations, but nothing has so altered him, nothing has led him to the thought that dawns on him now: This is all that I am. This is all I have to give.

Is The Hunter’s Tale my Tipu’s Tiger? Or am I still carving mine? Will I fare better than Abbas when the thing I’ve made belongs to someone else and is subject to their interpretation? Should the creation, in the end, matter to me more than the creating?

I have gotten at least one tattoo every place that I’ve lived. At this point, I’ve spent over three months in India, and next time I go I’ll be setting up an Indian bank account and getting an Indian phone number, so it seemed it was time for me to get a tattoo in India, provided it was with a particular Bengaluru artist that had been recommended to me and that it would be on the last day of my visit so I could just wrap it up and fly home and not worry about aftercare in a country that has given me a severe infection before. As it happened, my most recent trip was scheduled to end in Bengaluru. I contacted the shop and got an appointment for a tattoo of Tipu’s Tiger.

And then the day before my appointment, the artist fell ill with a fever and needed to cancel.

I was disappointed, having gotten myself psyched up for something that was, probably, an unnecessary risk but also a ton of fun. So, with a day to myself, I walked to Blossom Book House and browsed around for a while, disappointed not to find Tania James’s The Tusk that Did the Damage but finding a lightly used edition of Arundhati Roy’s The God of Small Things.

Back outside in the heat of the day, not sure what to do with the few hours remaining for me in the country, I realized how badly I wanted to get a tattoo, some kind of tiger tattoo even if it wasn’t Tipu’s Tiger specifically. I had gone too far with this plan, and it had already taken on meaning to me. Every tattoo I have says something about where I was in life when I got it (even the heart-shaped waffle), and this tiger suddenly felt like the perfect symbol for so many things I was feeling. So I looked up tattoo shops in my general part of the city and found one that had many high ratings and was recognized as being sanitary and professional. And wouldn’t you know it was a five minute walk down the same street as the bookstore. Fuck it, I said. Let’s see if they take walk-ins.

For the record, I do not advise getting a walk-in tattoo anywhere, least of all in another country. And I definitely do not advise putting yourself in a situation where you have to change the bandage in an airport bathroom before getting on an international flight. But let me tell you, my brother Infant at Micro Tattoo Studio absolutely fucking crushed it. And one month of healing later, I appear to have escaped any infection.

I understand very well now why the Taj Mahal, The Brutalist, and Loot mean so much to me. I understand why I’m having so much trouble getting the sequel to The Hunter’s Tale written. And I understand why, even faced with the total annihilation of real art, I am holding so desperately to the hope of writing something that will last. In a time of so much uncertainty I must, as an artist, build a fire each morning and begin again.

A few months ago, when I produced a hard cover edition of The Hunter’s Tale, I needed to revise the beginning of Lives We Might Have Lived so it could be included at the back of the book. Mainly, I needed to change all the verb tenses from past tense to match the present tense I had shifted to. This would be a pain to do manually, so I decided I would, for the first time, try using ChatGPT. I asked the program to switch all the verbs from past tense to present tense, and it did so instantly and with perfect accuracy. “Shall I go on?” it asked, having only done about half of what I copied and pasted. I asked it to, and it did.

And then, when I scrolled to the end of Chat’s output, I was horrified to find it had taken the liberty of continuing my story.

I closed the tab, not even bothering to save the work it had done for me, and began manually changing the verb tenses. I felt so intellectually violated, just sick to my stomach with what I had seen cracking a door just a few inches. I’d seen the face of the thing that is coming for me, for you, for us all, a vampiric force invited in by millions of users every day.

As we exited the inner chamber of the Taj, where the Empress and the Emperor are laid to rest and there is no photography allowed, I asked the guide a question I was surprised had not already been answered.

“So who actually designed the Taj Mahal? Who was the architect?”

“The architect?” said the guide. “Ah, hmm. What was his name…”

Forth now, and fear no darkness.

Soli Deo Gloria

Peter

P.S. Fuck you, Ayn Rand.